In preparation for the 1993 Vision-21 symposium held in Cleveland, Ohio, USA, NASA’s Lewis Research Centre issued a small press release. In it they explained:

Cyberspace, a metaphorical universe that people enter when they use computers, is the centrepiece for the symposium entitled “the Vision 21 Symposium on Interdisciplinary Science and Engineering in the Era of Cyberspace.” The Symposium will feature some remarkable visions of the future.[1]

Looking back it’s probably difficult to imagine the sort of excitement that surrounded symposiums built around this theme. Today our contemporary notions of a digitised reality centre on ideas of the social network and connectedness, in which one is either online or off. The Internet augments and points back to a reality we may or may not be engaged in, but it doesn’t offer an alternative reality that isn’t governed by the same rules as our own. The concept of cyberspace, or an immersive “virtual” reality in which the physical laws of our own do not apply, has all but disappeared from the popular consciousness. These days any talk of immersive digital worlds conjures up visions of social misfits playing non-stop sessions of World of Warcraft, or living out fantastic realities in Second Life. In 1993 cyber-hysteria was probably at its peak. In the previous year Stephen King’s virtual reality nightmare The Lawnmower Man was released in cinemas and grossed one hundred and fifty million dollars worldwide[2]. Virtual reality gaming systems, complete with VR helmet and gloves, were appearing in arcades everywhere (though they never seemed to work), the Cyberdog clothing franchise was growing exponentially and even the cartoon punk-rocker Billie Idol jumped on the bandwagon with his 1993 album Cyberpunk. Vision-21 was probably right on the money, dangling cyberspace as a carrot in order to draw big name academics, dying to share their research on ‘speculative concepts and advanced thinking in science and technology’[3].

Amongst the collection of scientists and academics, who I imagine paid their participation fees to deliver papers with titles like Artificial Realities: The Benefits of a Cybersensory Realm, one participant sat quietly waiting to drop a theoretical bomb. Vernor Vinge (pronounced vin-jee); science fiction writer, computer scientist and former professor of mathematics at San Diego State University, was there to read from his paper entitled The Coming Technological Singularity: How to Survive in the Post-Human Era. You can almost picture the audience’s discomfort as Vinge read out:

Within thirty years, we will have the technological means to create superhuman intelligence. Shortly after, the human era will be ended.[4]

The crux of Vinge’s argument, summarised for sensational effect in the two sentences above, was that the rapid progress of computer technology and information processing, ran parallel to the decline of a dominant human sapience. Technologies built to augment and increase humanity’s intellectual and physical capabilities, would eventually

develop a consciousness of their own and an awareness that our presence on earth was negligible. This series of events and the resulting set of consequences are what Vinge referred to as The Technological Singularity.

This dystopic future narrative, foretelling a kind of sinister digital sentience, had already been played out on the big screen in Stanley Kubrik’s 2001: A Space Odyssey and James Cameron’s Terminator (featuring Arnold Schwarzenegger’s career defining role as the ‘Micro-processor controlled, hyper-alloy combat chassis’[5], or cyborg for short). What rescued Vinge’s thesis, from the familiar terrain of dystopic cyber-plot lines, and a hail of academic derision, was the insertion of a second and more plausible path towards a post-human era. The traditional sci-fi route to the post-human condition has the sudden self-consciousness of superhumanly intelligent machines as its root cause. This formed part of Vinge’s initial argument.

If the technological singularity can happen, it will. Even if all the governments of the world were to understand the “threat” and be in deadly fear of it, progress toward the goal would continue. In fiction, there have been stories of laws passed forbidding the construction of a “machine in the likeness of the human mind”. In fact, the competitive advantage – economic, military, even artistic – of every advance in automation is so compelling that passing laws, or having customs, that forbid such things merely assures that someone else will get there first.[6]

Still, Vinge must have known that the creation of a superhumanly intelligent, sentient, computer was a bit of a long shot. Artificial Intelligence machines still hadn’t managed to pass Alan Turing’s test since it was introduced in 1950 and Japanese electronics seemed primarily concerned with teaching robots to dance. So in order to shore up this rather shaky portion of his post-human hypothesis Vinge introduced another pathway to the technological singularity called Intelligence Amplification (IA). What the expression refers to is a process in which normal human intelligence is boosted by information processing apparatus. Vinge explains:

IA is something that is proceeding very naturally, in most cases not even recognized by its developers for what it is. But every time our ability to access information and to communicate it to others is improved, in some sense we have achieved an increase over natural intelligence. Even now, the team of a PHD human and good computer workstation could probably max any written intelligence test in existence.[7]

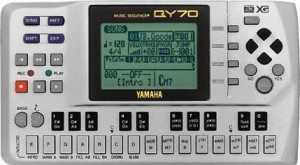

What Vinge sketches out above is the kind of hypothetical example in which chess grandmaster Gary Kasparov and Deep Blue, the computer programme that beat him at his own game in 1997, would have joined forces to become a superhumanly intelligent, post-human, chess player. It’s the clunky combination of a desktop computer and PHD student that makes the prospect of a superhuman chess-God so unthreatening. Even in 1993, nobody at the vision-21 symposium would have possessed a computer small and unobtrusive enough to amplify his own intelligence levels without everyone else in the room knowing about it. Today that’s a different story. What Vinge knew then was that at the accelerated speed with which reductions in computer hardware size (and their concomitant increase in processing power) were taking place, it would only be a matter of years before powerful information processing engines could fit in the palms of our hands, or even, further down the line, become interlaced with our brain’s axons and dendrites. He knew that the scientists and academics sitting in that room knew it too.

At it’s most basic, IA takes place when you check a digital watch or solve a difficult mathematical problem with a calculator. Today the amplification of intelligence is happening on nearly every street corner, in every major city in the world, courtesy of smart-phones and instant portable access to the Internet. The speeds with which developments in computer technology led to this newfound portability are unprecedented and show no signs of abating. If anything, developments are probably getting faster. Viewing social, political and cultural life through the lens of IA, there’s a pretty strong case for Vinge’s technological singularity and the idea that we are living through its latter stages.

But what’s so bad about progress? Wouldn’t it be cool if everyone was walking around with superhumanly amplified intelligence levels? Maybe so, but implicit in Vinge’s theory is an existence many of us would struggle to define as human:

The post-singularity world will involve extremely high-bandwidth networking. A central feature of strongly superhuman entities will likely be their ability to communicate at variable bandwidths, including ones far higher than speech or written messages. What happens when pieces of ego can be copied and merged, when the size of self-awareness can grow or shrink to fit the nature of

the problems under consideration? These are essential features of strong superhumanity and the singularity. Thinking about them, one begins to feel how essentially strange and different the post-human era will be, no matter how cleverly or benignly it is brought to be.[8]

The question of access to this superhuman capacity is also a cause for concern. As the possession of advanced technological apparatus is reserved for those who can afford it, will we begin to see the emergence of an underclass of sub-humans, stuck on average levels of intelligence? And what happens when the first instance of computer/human symbiosis takes place? Will the first fully awakened, integrated superhuman man/machine see his or her own flesh as the negligible half of that pairing? We’re heading dangerously into Terminator territory again, but as fantastic as these questions sound, they are entirely plausible. Whatever the case may be, as humankind hurtles towards it’s own obsolescence; accelerated reality is a disorienting place to be.

[1] //www.nasa.gov/centers/glenn/news/pressrel/1993/93_17.html

[2] http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0104692/

[3] //www.nasa.gov/centers/glenn/news/pressrel/1993/93_17.html

[4] VINGE, Vernor, The Coming Technological Singularity: How to Survive in the Post-Human Era, 1993

[5] CAMERON, James and HURD, Gale Anne, The Terminator, Screenplay, 1983

[6] VINGE, Vernor , (as above), 1993

[7] ibid

[8] ibid